In Bed-Stuy, the nation’s only minority-run volunteer ambulance corps rides the streets, and 911’s not a joke.

It’s 10 past four on a fast-cooling early Saturday morning and the red-eye crew of the Bedford-Stuyvesant Volunteer Ambulance Corps is sipping coffee in the back of the ambulance. Martin Law, 30, Timothy Sutton, 28, Angelina Coleman, 23,and 35-year-old Vivian Lomacang are regulars on the Friday night shift. They work to gain hardcore medical experience. They are rarely disappointed.

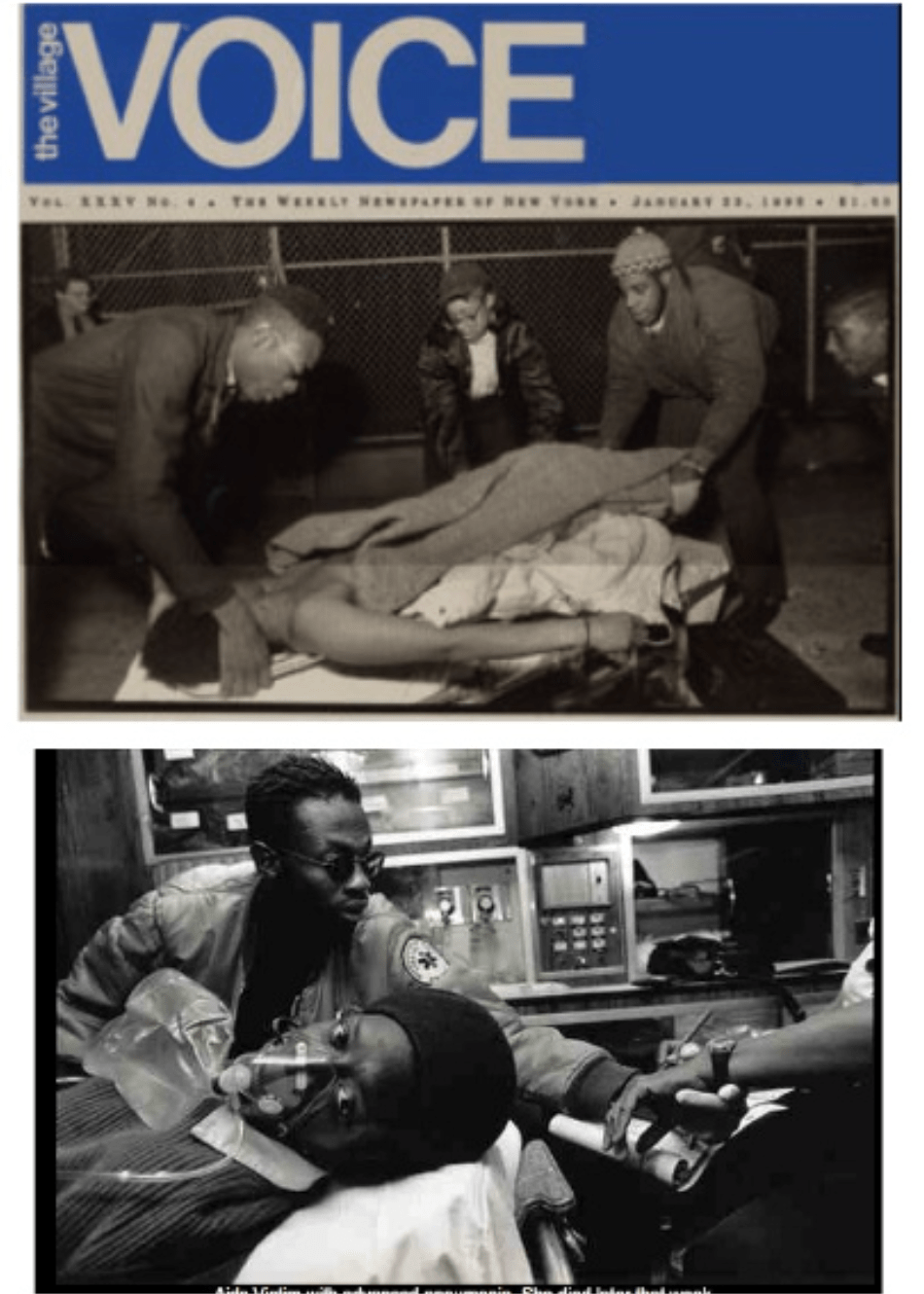

“Man shot. 1851 Fulton Street” — the police scanner crackles, the coffee goes flying, and the Bed-Stuy volunteer ambulance roars into life. The “man” is just a boy, 16 years old and shot through the eye on his way home from a graduation party. He is lying under a basketball hoop in the center of the Brevoort Housing projects, and police are on the scene as the volunteers arrive. The boy is surrounded by about a hundred onlooker who stand numbed and silent while the police chat complacently — they’ve seen too much of this already tonight. As Coleman and Lomacang unload the backboard and stretcher, Law applies a neck brace to the boy and tries to calm him as he cries out in the a mixture of shock and pain. Behind him, a distraught relative keeps pleading to anyone who will listen, “Could you all stand back and give him some air, please.”

EMS paramedics arrive and together the crews gather round the young boy and life him slowly onto the backboard, then onto the stretcher. Both teams help carry the boy to the Bed-Stuy ambulance and one of the EMS medics jumps in with the volunteers. Inside, the crew tries to stabilize the boy. “Quincy…how you doing, Quincy…try to breathe when she pumps that thing,” urges the paramedic as Lamacang gives oxygen to the patient. They reach Kings County Hospital in less than 10 minutes, the boy’s family following close behind. Quincy is admitted to the overflowing trauma center. “Don’t stay out late with all that money,” his grandmother had warned him as he left for the evening. “They’ll get you if you got money or if you got nothing…” he had said. “It don’t make no difference.”

In an abandoned lot, under the gaze of the adjacent crack houses, sits a 55-foot read-and-white trailer, the door always open and with an attitude the drug dealers can’t destroy. This is the headquarters of the Bedford-Stuyvesant Volunteer Ambulance Corps, the first minority ambulance corps in America. Inside site its founders, Lieutenant James “Rocky” Robinson, 50 years old and a medical supervisor at nearby Woodhull hospital, and Joe Perez, a registered health care instructor and an EMS employee for more than 10 years. A little over two years ago, the two men formed the Bed-Stuy Corps in response to a chronic shortage of health care in the neighborhood and with the intention of combating what they saw as a war in their own community.

“Guerrilla Healthcare,” they call it, as they relax in the back office of the trailer, on the corner of Greene Avenue and Marcus Garvey Boulevard, formerly known as Sumner. “We had this guy this morning come running down here grabbing his neck…two guys following him. He was bleeding so bad…” bellows Robinson with some glee, describing what had happened earlier. “I run out and put my had on his neck to stop the bleeding and while I’m helping, he starts trying to fight again with the other guys…I tell you it’s crazy here.” In the background, police and EMS radio scanners fight for his attention with the TV evening news and the sound of the ever-popular Pac-man machine.

Outside the corps, the familiar sounds of Bed-Stuy fill the night: the booming bass speakers of passing cars and the laugher of the men standing outside the El Dorado Suprette on the other side of the street, drinking beer out of brown paper bags. On the steps of the trailer sits Mark Johnson, 30 years old and an Emergency Medical Technician (EMT) for a private ambulance firm in Queens. He is tall and lanky, sporting Brooklyn’s current favorite haircut — short dreads with shaved sides. Mark is a serious man, and wary of outsiders interested in his neighborhood. He’s been with the corps for over a year but now only comes when his job allows. As he sits and chats, a woman comes up, drunk and faltering slightly in her walk. Her name is Bobcat and she looks about 40, but is probably younger.

“Where you been Bobcat?” asks Johnson. “Oh, I been in the hospital,” she replies as she lifts her head by means of explanation, revealing a six-inch scar running from her ear down under her chin. “I got jumped one morning by my man and I never saw the kitchen knife in his hand.” Johnson nods to Bobcat with a sense of resignation and starts playing catch with a group of children next to the always-leaky fire hydrant. They throw a football back and forth as Bobcat weaves her way down the sidewalk.

Bed-Stuy has the second largest black population of any neighborhood in the U.S. after Chicago’s South Side. Originally the site of a Dutch sheep-farming project, Bedford-Stuyvesant has been the home of the African-American community for well over 200 years. Bedford and Stuyvesant were originally separate neighborhoods: Bedford a mainly white middle-class area, Stuyvesant part of the early free black communities of Weeksville and Carrsville. Not until the 1880s and the opening of the Brooklyn Bridge did the neighborhoods begin to expand, as both whites and blacks moved into New York’s newest borough. With that growth, relations between the two racial groups deteriorated. By the late 1920s, both blacks and whites were arming themselves, ready to protect their territory. In 1931, the Brooklyn Eagle first grouped the two communities together, referring to them as Bedford-Stuyvesant. From then on, the name stuck.

By 1950, most of the white residents had moved out, taking with the money that kept the neighborhood affluent. Since the ‘50s, drugs have invaded the community. In the 1960s it was heroin; in the ‘70s cocaine; now it is crack.

In 1988, James Robinson and Joe Perez decided to fight back. They were concerned about the medical needs of Bedford-Stuyvesant and about the inability of the state-run EMS to serve their community.

In 1989, there were 100 homicides reported in Bedford-Stuyvesant. Since June, 32 children have been shot citywide, caught in the crossfire that is commonplace in New York’s poorer areas. Many of the people in those communities complain about the poor response time of the city’s Emergency Medical Services, a problem highlighted by Public Enemy’s “911’s a Joke.”

“I remember going on calls when I first started here and they [EMS] wouldn’t show up at all,” says Deborah Crawford, a 37-year-old mother of seven who recently qualified through training with the corps as an EMT. “EMS is overburdened and the people who are suffering are in Bedford-Stuyvesant,” added Robinson. “People in this community are not going to get the quality care that they do in Queens…Why are calling 911 and playing Russian roulette with our children’s lives?”

EMS has long been the target of both professional and public criticism. Since as long ago as 1978, horror stories of ambulance ineptitude were filling the pages of the New York dailies. “Dial 911. Then Wait…” ran one Daily News headline in 1978, while a second Newsarticle written in 1981, and entitled “HOW TO SAVE YOUR OWN LIFE” offered this helpful advice to an ailing New York community: “Depending on the severity of the emergency and the distance to the nearest hospital, you might consider hailing a taxi.”

Only last month, new evidence emerged regarding the case of schools chancellor Richard Green, who died last year of an asthma attack before EMS crews could reach him. WNBC has acquired a recording of an EMS dispatcher dissolving into fits of giggles as she attempted to send an ambulance to Green’s West 61st Street home. Perhaps more alarming was EMS’s comment that her actions did not affect the call and that she received only a written reprimand.

Back in 1980, the average response time for EMS ambulances involved in priority-one calls — heart attacks, severe bleeding and other acute emergencies — was 16 minutes. The then vice-president for EMS said his goal was to have ambulances respond within 10 to 12 minutes. Ten years later, EMS has achieved that goal, but even 10 minutes is not quick enough to save cardiac victims who, most experts agree, need to be reached within six minutes. A 1987 study, commissioned by then City Council president Andrew Stern and titled New York City’s Emergency Medical Service: An Agency at Risk, reported, “As emergency systems throughout the nation continue to improve, New York’s EMS grows more and more deeply troubled.”

There are no response breakdowns for the borough of Brooklyn, only for the city as a whole, but both Robinson and Perez estimate that when BSVAC began it would take and EMS ambulance up to 20 minutes to reach a Bed-Stuy call: BSVAC maintains an average response time of four minutes, the difference between life and death in many cases. Today, Robinson says that the city service now responds to calls in Bed-Stuy in about seven minutes. The volunteer organization says that its presence, and the media attention it has attracted, has prompted EMS to increase the number of crews assigned to Bed-Stuy.

“That is no valid,” says Lynn Schulman, spokesperson for New York EMS, asserting that Bed-Stuy has been given no special privileges. She also denies that EMS has been placed under pressure by the renegade volunteer group. “We get a million calls a year at EMS and the volunteer organizations of the city handle only about .02 per cent of those.” What cannot be denied is the regular presence of an EMS crew stationed outside the volunteer’s headquarters on Friday and Saturday nights. As Rudy Boyd, BSVAC Chief of Operations and himself a member of EMS , puts it, “EMS must be thinking, ‘OK guys, we’d better get our shit together ‘cuz these guys are making us look like shit!’”

TWO-THIRTY A.M., no time to relax. The coffee, courtesy of Mama’s Fried Chicken, is flung aside as the Friday night crew responds to an assault just three blocks away. A homeless man, his face covered with a mixture of dried blood and fresh gashes, is led to the ambulance by two police officers. The man has been attacked with a lead pipe and is bleeding profusely. As he is helped into the bus — medical slang for ambulance — he collapses on the stretcher and his eyes roll to the side.

“Can he open his mouth?” asks Timothy Sutton, a trained EMT, as the other members of the crew check the man’s vital signs.

“Can you open your mouth like you’re yawning?Ah, not too good,” replies Law. Martin Law is one of the few white members of the corps and works for a private ambulance firm on Long Island. He is English and came to New York five years ago with no medical experience. Tonight, he is the chief tech for the shift. He comes every Friday night because, as he puts it, “I guess I just like caring for people.” He must be back at work Saturday morning by nine.

Sutton picks up the radio and speaks: “Bed-Stuy 4 to bas, be advised, the patient’s BP is dropping, we have a BP of 90 over 68…we’re going to up triage and MAST trousers are being applied.”

The MAST trousers take the role of a blood pressure straitjacket, ensuring that blood gets to the vital organs. They are used in gunshot and other trauma calls. In the back of the ambulance, the homeless man is drifting in and out of consciousness and is losing blood fast. Lomacang and Law, both sweating heavily, struggle to put the MAST trousers on him, fighting against the violent rocking of the bus and the stench of the patient. Angelina Coleman tries to keep the oxygen mask applied to the man’s face as Sutton races to Kings County Hospital. Law is thrown like a doll to the back of the bus; he screams something at his driver, but it is lost in the noise of the sirens. The radio crackles into life as the oxygen cylinders rock wildly and the cervical collars swing like traffic lights in a storm.

“Base to Bed-Stuy 4, be advised, we have KC on standby and there are two other calls going in there also…so let’s make this good.” Sutton kills the siren as they near the hospital’s trauma center and the man is admitted.

OFF DUTY, THE MOOD AT THE BASE is electric, and the trailer filled with laughter and tales of previous encounters. “Yahya, we could have done with you here last Sunday night,” says tonight’s crew chief, Deborah Crawford, to Yahya Rahim, a weekend volunteer who provides security for the corps. Rahim is about 50 years old and a devout Muslim. He runs a private security firm and rides with the ambulance at night to ensure the safety of the techs when they enter the dark stairways of the projects and neighborhood crack houses. “We got this shooting call,” she continues, “and when we got there and opened up the back of the bus, one of the gunmen started using the door as a shield and pointing the gun at us. Well, we was on the floor of the bus and for a moment I thought he was going to get in with us!” Rahim, a man of calm and deliberate actions, with thick glasses and pointed beard, says dryly, “Yeah, and what could I have done…?”

The Bedford-Stuyvesant Volunteer Ambulance Corps, despite its achievements in the neighborhood, is not universally popular. First, the drug dealers living next door complained — they said the noise of the ambulance was keeping them awake at night. Then it became apparent that local EMS didn’t welcome the competition. Two years after BSVAC’s inception, there is no disguising the antagonism between these two compassionate organizations.

James Robinson had been a medical supervisor at the EMS dispatch site at Woodhull Hospital for over 10 years, when, last year, he was transferred out of the borough and sent to Elmhurst Hospital in Queens. He has since been moved back to Bed-Stuy, but he believes thing have been made deliberately difficult for him to run the volunteer organization. “If you’re a member of the Bed-Stuy vollies, then you’re not going to be too popular with EMS management,” Robinson says.

The Bedford-Stuyvesant community is benefiting from the increased competition in emergency service: a bizarre kind of free-market health care where the quickest ambulance to the scene wins the patient, and in which EMS has been frustrated. At the same time, the normal good nature of an ambulance crew can be quickly eroded when at each call a rival crew has beaten them to it.

“Oh, Bed-Stuy, though you only turned up for shooting calls,” says one EMS paramedic as the volunteers arrive at a fifth-floor apartment on the corner of Nostrand and Park. It’s 11.30pm, Wednesday, and the crew has responded to a call at the Marcy projects. “No, we leave that to EMS,” responds Bed-Stuy tech Rudy Boyd, a daytime EMS colleague of the paramedic. The Bed-Stuy Corps responds to emergency calls by monitoring EMS calls on a scanner and by borrowing a police department radio every night from the 79th and 81stprecincts. In essence, it responds to exactly the same calls that are given to EMS ambulances. Robinson believes the tensions between the two services are inevitable. “There always will be hostility,” he says, “you’re never going to love the competition.”

Not all encounters are so hostile. On a hot Friday night as the red-eye crew prepares for its first call, Coleman, Lomacang, Law and Sutton respond to a 10.13 — officer in need of assistance. At the scene, the officer who made the call stands over a black male, aged about 35, lying on the ground, with a single clean bullet hole about the size of a small birthmark in the top of his head. EMS medics and a fire department basic life support unit are already at the scene. “Bed-Stuy here?” asks one of the medics, looking up and seeing the black, red and green of the corps caps, “Hey, no audience participation, come give us a hand.” Law and Coleman join the EMS crew and the whole group life in unison as, forgetting allegiances for the moment, walk the stretcher to the EMS bus. The medics ease the patient into the stark surroundings of the ambulance and the door is closed.

SAVING LIVES is just one of the Bed-Stuy vollies’ goals. They also want to educate the community and to train minority recruits as EMTs. The corps has more than 100 active members and has trained more than 30 EMTs. As Deborah Crawford puts it, “I once thought I would be home watching soap operas and collecting a welfare check, but now my goal is to become a paramedic.” Bed-Stuy also has a 12-strong youth corps, whose members attend advanced first aid classes three times a week and also perform community service for the elderly in the neighborhood. Their training includes the first part of the state EMT examination, which they can complete once they reach 18.

Youth corps chief Kassem Ali, a handsome and serious 17 year old, spends all his free time at the corps headquarters and is convinced this is the career for him. “I want to become a medic, then a doctor,” he says. ” I wish more people like myself would join and support their neighborhood instead of tearing it down.” Robinson believes that without the support of the corps, Ali, along with other volunteers, would have stood little chance of breaking into the medical profession. As he describes it, the obstacles to minority advancement in the EMS system are deeply rooted and will not disappear overnight.

“If you’re a big black dude from Bed-Stuy and you don’t have the right attitude — an attitude that doesn’t fit in, then you’re out of there man,” says Robinson, leaning back in his chair, his expression part contempt for the system and part smirk. EMS now claims 45 per cent of its “on the street” personnel are minorities. But all new recruits must train for at least one year with a volunteer ambulance corps before qualifying — and Bed-Stuy is the only minority run corps in the country.

In the 1970s, EMS was made up predominantly of blacks and Latinos. “EMS was punishment for minorities who messed up in the hospital,” says Perez. “All you needed was a driver’s license and some first-aid training. The salary was minimal. The job was not attractive to whites.” Then, in 1974, the service was completely restructured, shifting its emphasis from a “scoop and run” principle to mobile treatment. EMS placed more emphasis on triage — a series of vital signs checks to eliminate unnecessary delay at the hospital. The changes increased the appeal of EMT jobs and made compulsory the one-year training program with a volunteer corps. With few volunteer training opportunities available to minorities, black and Latino jobs in EMS dropped from 90 per cent in 1974 to less than 40 per cent by 1988.

With the appointment of Thomas Doyle as executive director of New York EMS in 1988, EMS attempted to improve its dealings with minorities and also its public image. As EMS spokesperson Schulman asserts. “Much has been done to improve minority recruitment and promotion in EMS…We will continue to work with the Bedford-Stuyvesant Volunteer Ambulance Corps and other organizations to further these improvements.

TWO YEARS AGO, when Perez and Robinson founded their corps, they were considered lunatics by their neighbors. Operating out of a second-floor apartment on the corner of Greene and Marcus Garvey, they had one ambulance, donated by a nearby corps, and a crew of about 10 volunteers. In the first year, after they had moved across the street to the trailer, they often spent entire weekends on call. For over a year, as Rudy Boyd describes it, they were operating “with no damn heat, no damn water, no bathroom and [being] stuck in here for two to three days at a time.” The bullet holes along the side of the trailer attest to the sometimes violent nature of their location. Sergeant Leroy Counts, community affairs officer of Bedford-Stuyvesant’s 81st precinct, believes that people were at first wary of the corps’ ability and commitment but now, he says, ‘There is a definite sense of pride in seeing a volunteer corps run strictly by Afro-Americans.”

The corps is always open and the volunteers handle seven to eight walk-in calls everyday — “treat and release” — as they are known. Most of the walk-ins are patients who haven’t got the time — or are afraid — to go to the hospital. Men and women cut up in fights, blue babies, and the normal band of hangers-on, just there for company under the pretense of a fever or high blood pressure. As Sgt. Counts points out, in an area where crime and crime-related injuries have increased dramatically, “People like the idea that they have a personal service and confidence in BSVAC has grown over the years.”

If you use drugs of if you are a habitual alcoholic or if you refuse to follow orders…then you will be asked to turn in your shield.” This is the warning that James Robinson gives to all new recruits of the Bed-Stuy Corps. Robinson is a satisfied man. At six foot four and over 270 pounds he is a formidable figure and nobody doubts who’s boss. “Yeah, I sleep real well at night,” Robinson says as he leans back in his chair, the Mets game blaring in the background. The corps has just been awarded a hefty grant from the Robin Hood foundation, and is presently negotiating with the city to acquire the lot they rent. Earlier in the summer BSVAC was part of the emergency medical backup for Nelson Mandela’s visit to New York.

The corps has also proved to be a big media success. Local TV stations have been quick to experience the “Bed-Stuy miracle.” Just two weeks ago, ABC’s 20/20 show profiled the corps. It’s this sort of coverage that has supported the volunteers until now. It costs the corps more than $10,000 a month to keep one ambulance on the road. To raise that money, they’ve turned to foundations and community fundraisers. They have organized trips to Atlantic City, held various parties featuring celebrities such as Mets’ stars Darryl Strawberry and Sid Fernandez and have gone around the neighborhood collecting with a bucket. The members have been courted by Hollywood producers eager to buy the rights to the “Bed-Stuy story” but at present, the plans are more down-to-earth: Opening a second office in the neighborhood and forming a new all-minority private ambulance service in Brooklyn.

“I call it B-S syndrome” says Hejazi, a new recruit from Staten Island who can’t stay away from the Bed-Stuy corps. Hejazi laughs as he talks about how he drives the 40-minute trip to Bed-Stuy sometimes five nights a week after work. He is an electrician by trade and started working security for the corps on dangerous calls. Like the other vollies, Hejazi soon got hooked on becoming an EMT and the thrill of saving lives.

“My wife says, ‘Hejazi, you were crazy when I married you and you’re still crazy now,’” Hejazi retells with a smile.

ON A BUSY FRIDAY NIGHT, a young girl sits on a chair outside the corps trailer, tears rolling down her face and accompanied by her best friend. She is Latina, and very pale, her long jet-black hair accentuating her unnatural pallor. The street is full of people — it’s too hot to stay inside tonight. The girl is 13 years old and pregnant — four months she thinks. She hasn’t told her mother about her baby, nor about her previous miscarriage. She has been hit in the stomach as she tired to break up a fight between her mother and her boyfriend and now she looks lost and afraid. Crawford tells her she has to go to the hospital, but without her parents, she must be accompanied by the police. Crawford agrees to drive the girl to Woodhull where they will meet the police and she is slowly helped up into the ambulance, placed on the stretcher and strapped in, all the time clutching what life is left in her stomach. The ambulance doors are closed and it leaves for the hospital. Painted on the back is a message from the Bed-Stuy volunteers. It reads simply, STAY ALIVE.

This story was first published in The Village Voice in 1990.

Leave a comment